Karl-Marx-Allee (Karl Marx Avenue) is a monumental socialist boulevard built in stages by the GDR between 1952 and 1960 in Berlin. It was East Germany’s flagship reconstruction project after the Second World War. Its initial construction celebrated the 70th anniversary of Stalin’s birth, which led to the promenade being named Stalinallee (Stalin’s Alley). A decade later, during Khrushchev’s de-Stalinisation campaign, it was renamed the Karl-Marx-Allee that we know today.

Karl-Marx-Allee starts at Alexanderplatz and stretches for almost 3 km to Friedrichshain. At 90 m wide, it gives the impression of being more powerful than Paris’ Champs-Elysees. Before being named Stalinallee, the boulevard was called Große Frankfurter Straße. At the time, it was one of the district’s main streets, lined with stately townhouses. During the Second World War, Berlin was severely damaged – including the eastern district of Friedrichshain. During the post-war reconstruction, it was decided to turn the former Große Frankfurter Straße into a representative avenue – the pride of the reborn East Germany. In order to give its creators the best possible suggestions for a unique design, a government delegation travelled to Moscow, Kiev, Stalingrad and Leningrad in 1950 to study Soviet urban planning and architecture. The project was designed by Egon Hartmann in collaboration with architects Richard Paulick, Hanns Hopp, Karl Souradny and Kurt W. Leucht, as well as Moscow’s chief architect Alexander V. Vlasov and Sergei I. Chernyshev, vice-president of the Academy of Architecture. The representative buildings were erected to house spacious and luxurious flats for the working class, as well as shops, restaurants, cafés, a tourist hotel and the huge Cinema International.

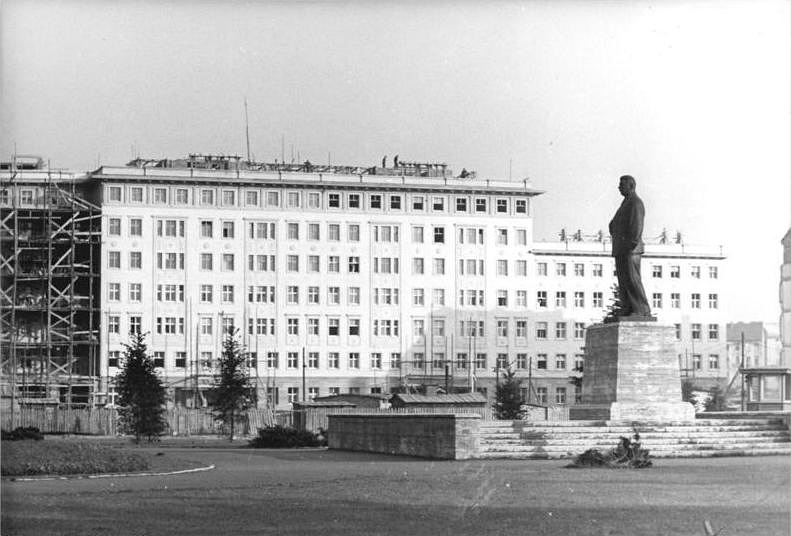

A view of Karl-Marx-Allee. Source: Ruslan Taran, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Four million hours were worked on the construction and more than 38 million bricks were used. The foundation stone was laid by the first prime minister of the GDR government, Otto Grotewohl. The enormous palace-like buildings with lifts and social-realistically decorated facades, staircases and colonnades at the gates provided 2767 flats with parquet floors, hot water and central heating. At either end of the avenue – at Frankfurter Tor and Strausberger Platz – are twin towers, designed by Hermann Henselmann. The buildings are distinguished by their facade decorations, which incorporate traditional Berlin motifs by Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Most of the buildings are clad in architectural ceramics, which further adds to their splendour. The avenue has been developed with both monumental eight-storey buildings designed in the style of Soviet Socialist Classicism and simple eight- to ten-storey prefabricated blocks with wide green areas on the street side and in between, which date from a later period. The main reasons for the change in architectural style were the high construction costs of the representative workers’ palaces and the transformation of the prevailing patterns of the time.

The neighbourhood of Große Frankfurter Straße in 1928 and Karl-Marx-Allee in 2015. Source: 1928.tagesspiegel.de

on 3 August 1951, a monumental statue of Stalin was ceremonially dedicated on the new avenue. It remained there until 1961, when it was removed as part of de-Stalinisation, which also resulted in the street being renamed after the founder of Marxism, Karl Marx. Later, the street was used for East Germany’s annual May Day parade, in which thousands of soldiers participated along with tanks and other military vehicles to show off the power and glory of the communist government. Once completed, the boulevard was very popular with Berliners and tourists alike. Shopping on Karl-Marx-Allee was a characteristic part of daily life in the capital. Things could be found there that could not be obtained elsewhere, and the shopping facilities became an example for the whole of the GDR. The shops offered a great variety and were attractively decorated. You could relax in cafés like Sybylle or the Kosmos cinema, and in the evening you could take your guests to one of the representative restaurants with such peculiar names as Warschau, Bukarest or Budapest. The boulevard also had the ideological function of introducing visitors to the culture of the ‘socialist sister states’.

By 1989, the oldest buildings were in need of a major overhaul. Half of the tiles had fallen off their facades, necessitating the erection of protective structures over the pavements in some places to protect pedestrian safety. The boulevard received great praise from postmodernists, with Philip Johnson describing it as ‘true urban planning on a grand scale’, while Aldo Rossi called the avenue ‘Europe’s last great street’. Since German reunification, most of the buildings, including the two characteristic towers, have been restored. The buildings of the foundation are sometimes densified, respecting the layout designed decades ago. From time to time, the topic of restoring the street’s name to the pre-war Große Frankfurter Straße also recurs.

Today, several decades later, the value of the foundation is unquestionable, and in professional circles it has long since gained recognition as an important trend in post-war European architecture, although since the fall of the Stalinist era it has often been underestimated and referred to by Berliners as “confectioner’s architecture”, “a confectioner’s dream” or “wedding cake” due to the ornamentation of the facades and façade finishes. It took half a century for the qualities of this building to be appreciated.

Source: dw.com, visitberlin.de, pawelwronski.blog

Also read: Architecture | Social realism | Estate | Urbanism | City | Block | Berlin | Germany