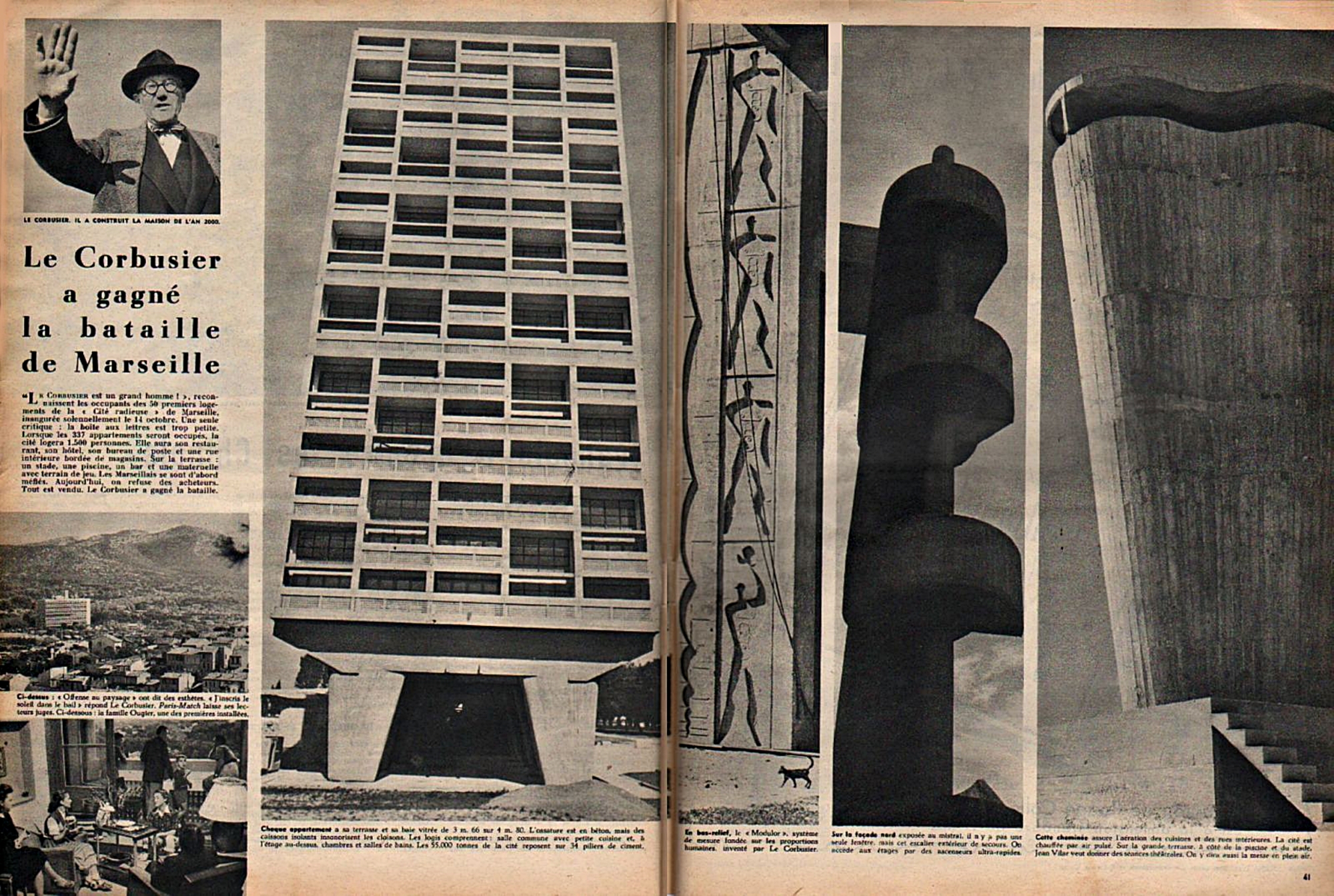

on 14 October 1952, the handover of the Unité d’habitation (Polish: housing unit) to the State and the municipal authorities of Marseille took place. “I hereby present the first building that meets the needs of modern life, made for man and on a human scale” – these were the historic words of its chief designer Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, better known by his nickname Le Corbusier. The event was a milestone in modern architecture. The architect revolutionised both the thinking about living space, urban development and material. The blocks built on the model of the Marseilles prototype are still admired today for their innovation and ever-present values.

The Unité d’habitation, also known as the Cité radieuse (Radiant City), was commissioned by the state and was a response to the huge demand for housing in post-World War II resurgent France. It is in fact a massive apartment block. Its dimensions are 137 metres long, 56 metres high and 24 metres wide. It has 18 floors and 337 flats for 1,600 residents. Situated in a park, the unit rises on a dozen massive pillars called pilotis. Between them is a free space conceived as a parking area for bicycles and cars and a pedestrian route. The support of the building gives the massive structure the optical impression of lightness. In addition to housing, the building contains shops, a library, sports facilities, medical and educational facilities, a 40-seat cinema and a hotel and restaurant.

Berlin type Unité d’habitation. Photo by Gunnar Klack, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

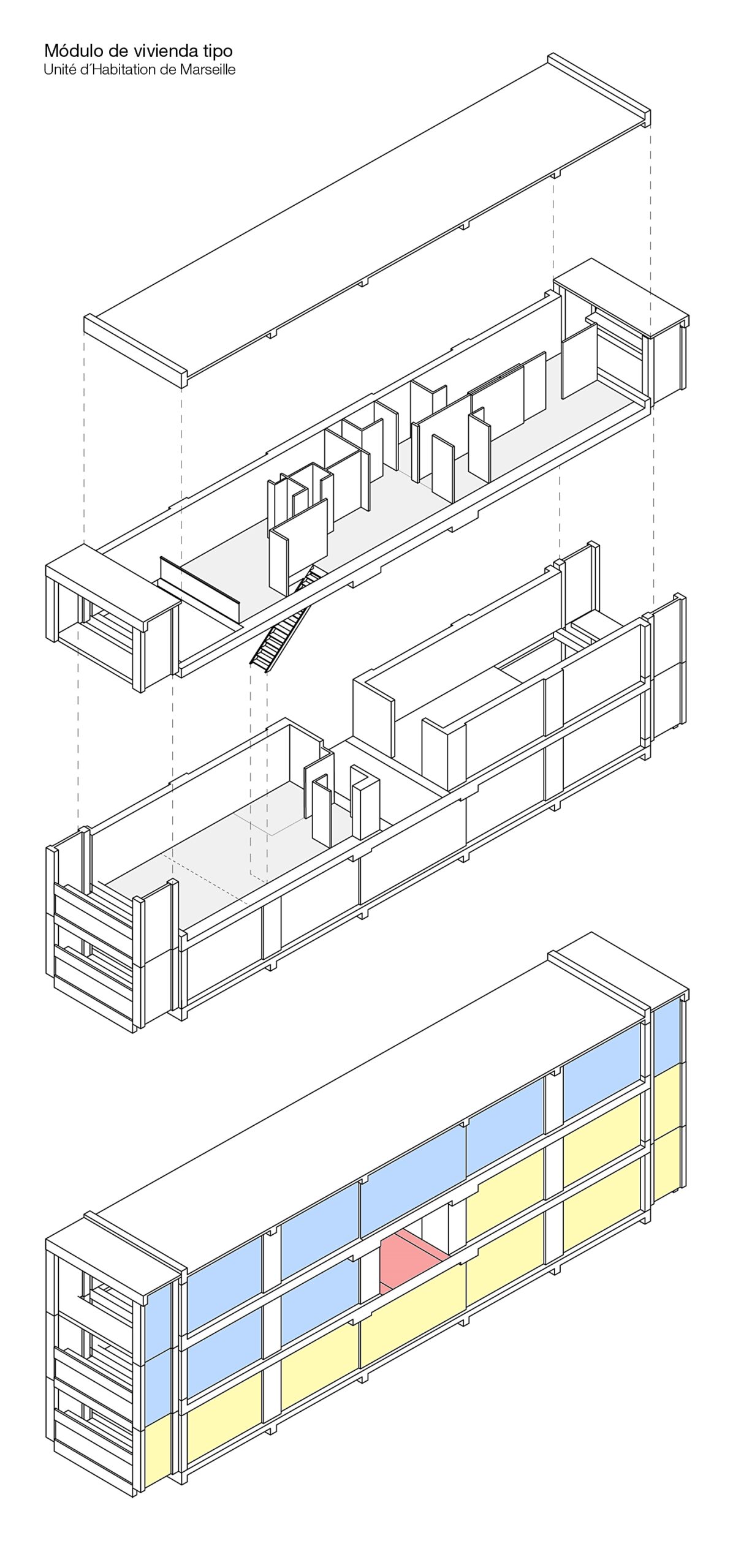

The flat roof was designed as a public viewing terrace and garden with a public panorama of the Mediterranean and the mountains on the opposite side. It also acts as an agora and resembles the captain’s bridge on a transatlantic liner. Above the roof, a sky bridge (French: belvédère) is visible, which extends beyond the outline of the ceiling. The dimensions of the flats were worked out thanks to Le Corbusier’s own way of measuring space called Modulor, based on human dimensions, the golden division and the Fibonacci sequence.

Le Corbusier and his team designed 23 different types of flats, ranging from studios to flats designed for a large family. The average flat size is 98 m². Each kitchen is equipped with a rubbish chute, which is itself an innovative installation. Each flat has two levels, windows on two sides of the world, oak parquet flooring, is equipped with several spacious loggias acting as small gardens (fr. le petit jardin) and is completely glazed thanks to portfères installed in rows in each room. The interiors have been designed according to Le Corbusier’s inspired ideas of monastic and naval architecture; rationalism and simplicity are noticeable.

The longer facades resemble a colourful truss in their appearance. It is a series of balconies and deeply set windows, whose rows mark the layout of the floors. The inner walls of the loggias are painted in vibrant colours: red, blue, yellow, green. These contrast with the overriding colour of the façade, which is the light, rough grey of the concrete. Leaving it in its raw state (béton brut) became the impetus for the birth of a new style and a new philosophy of architecture called brutalism.

In developing the facades of the Units, Le Corbusier introduced alternating rhythms, the recesses of the loggias allowing the play of light and shadow. Massive balustrades, columns and chimneys and lift shafts were given rich, almost sculptural forms.

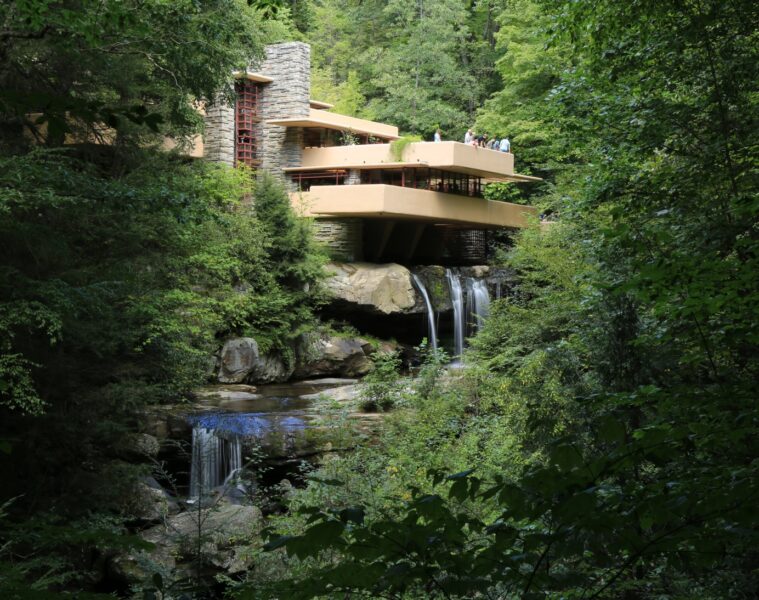

This project was repeated by Le Corbusier outside Marseille in four other buildings of the same name and very similar design. Housing units were also built in Nantes-Rezé (1955), Berlin-Westend (1957), Briey (1960) and Firminy (1967). The unit is also considered the prototype of the apartment blocks built in communist countries. These, however, were realised in a distorted and misunderstood version. They were, in fact, a negation of Le Corbusier’s thinking on functional architecture.

The block is an icon of 20th century modernist thought. The Unité d’habitation in Marseille was protected as a monument of French history as early as 1964. In 2016, it was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as part of the site: Le Corbusier’s architectural works as an outstanding contribution to modernism.

Source: isztuka.edu.co.uk, urbnews.co.uk

Read also: France | Modernism | Brutalism | Facade | Block