The author of the project is Jakub Masłowski, a third-year student of Architecture at the Białystok University of Technology. He prepared the project as part of the international Łobzów Courtyard competition. Although his concept of the Łobzów palace did not win the competition, it attracted the attention of the jury, which mentioned the student’s project as worthy of special attention in its conclusion.

The competition consisted of an architectural and urban design concept of a multifunctional didactic building for the Faculty of Architecture at the Cracow University of Technology at 1 Podchorążych St. A total of 70 pairs were submitted, and the first prize went to Piotr Mazur, a student of the Faculty of Architecture at the Cracow University of Technology. Below, however, we describe Jakub Masłowski’s project.

The Łobzów Palace, once a royal residence, tells a story dating back to 1357, when King Casimir the Great commissioned the construction of a Gothic castle near Krakow. Over the centuries, it has undergone numerous changes of ownership, resulting in significant transformations. Particularly during the reign of Queen Bona Sforza, the palace took on an “Italian” character, and in the second half of the 16th century, the Italian architect Santi Gucci was given the task of transforming the Gothic building into a Mannerist-style palace. The arcades connecting the west and east wings then became a unique feature, serving both an aesthetic and practical function by enclosing a courtyard for privacy. Unfortunately, the 17th-century Swedish invasion of Poland brought tragedy, leading to the palace being sacked and severely damaged. Despite its decline from its former glory, the palace continued to be a prestigious place for the Polish royal family, hosting such well-known figures as Maria Kazimiera awaiting her husband, Jan III Sobieski, after the Battle of Vienna.

After the partitions of Poland, the palace’s importance deteriorated. In the 19th century, its size increased considerably leading to the present shape of the building. When approaching the palace from the courtyard, the arches immediately catch the eye, revealing themselves as arcaded windows, doors and friezes, alluding to the historical presence of the arcaded gallery surrounding the courtyard.

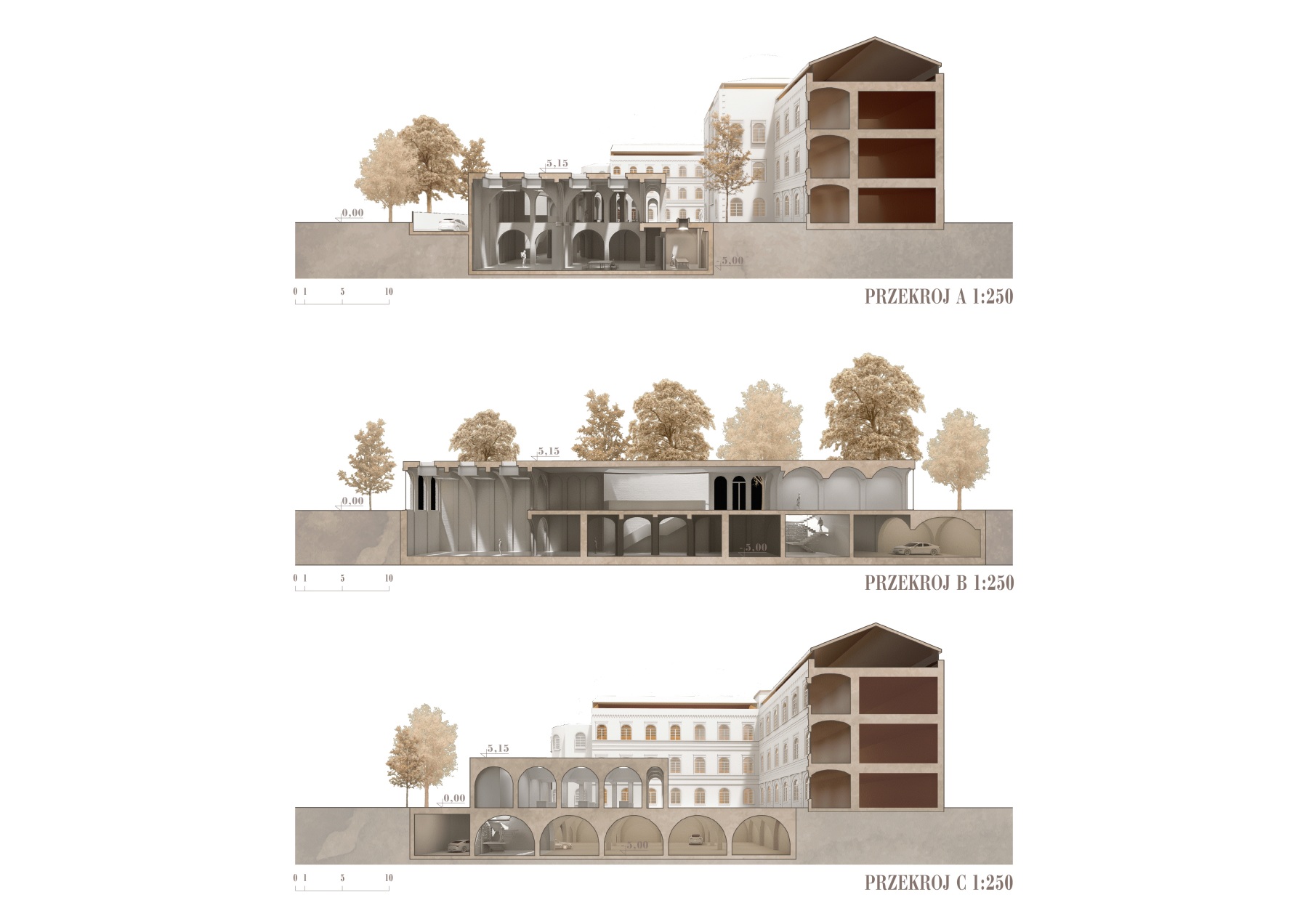

Arcade courtyards were common in this part of Poland, as can be seen in buildings such as the castle in Niepołomice or Piaskowa Skała, as well as in buildings in Kraków like the Wawel Royal Castle. The choice of arches at the time was due to the limitations of using brick. Unlike concrete lintels, brick cannot close the opening in a straight line, requiring the use of arches to take advantage of compressive forces along the curve. Although Łobzów Palace hides its brick structure beneath the render, the deliberate use of brick, in the newly designed building, as a distinct element pays homage to the original building material. In the spirit of Louis Kahn’s wisdom that ‘brick doesn’t like to be painted’ and ‘brick likes an arch’, the design celebrates the inherent qualities of brickwork. The focus on arches goes beyond mere formal aesthetics; they become integral structural elements that shape the entire building. This approach, which emphasises the understanding and use of materials based on their inherent properties, provides a valuable lesson for aspiring architects.

Recently, the notion of context has been overused in architectural criticism, and architects have institutionalised this notion with a design methodology that is based on analysing the environment in which a project is created. For those who practise such a method, architecture becomes the simple result of this analysis: the building is practically created under the dictates of the context and is understood as the conclusion of a syllogism whose premises are determined by place. To understand the place-architecture relationship in this way is to establish a hierarchical order that ensures the harmonious interaction that occurs between one and the other during the construction process. Using the same means of construction, using identical techniques, has always seemed the most respectful way to coexist with the existing historical context. Faced with the dilemma between replication and persistence in the orientations defined by the existing building, it was the latter that prevailed. But the use of quasi-historic means of construction such as arch, brick, does not exclude the contemporaneity of the architectural form, thus creating a counterpoint in which the appeal of the project lies.

When designing in the vicinity of historic buildings, it is important to ensure that the existing part can be distinguished from the newly designed part. This can be achieved through a radical juxtaposition by contrast, or balance and harmony can be sought between the two buildings. An example of a successful harmonious symbiosis is the Museum of Roman Art in Mérida. The great Spanish architect, Rafael Moneo, demonstrates the beauty of an architecture that draws handfuls from Roman construction techniques, yet the building is unmistakably modern.

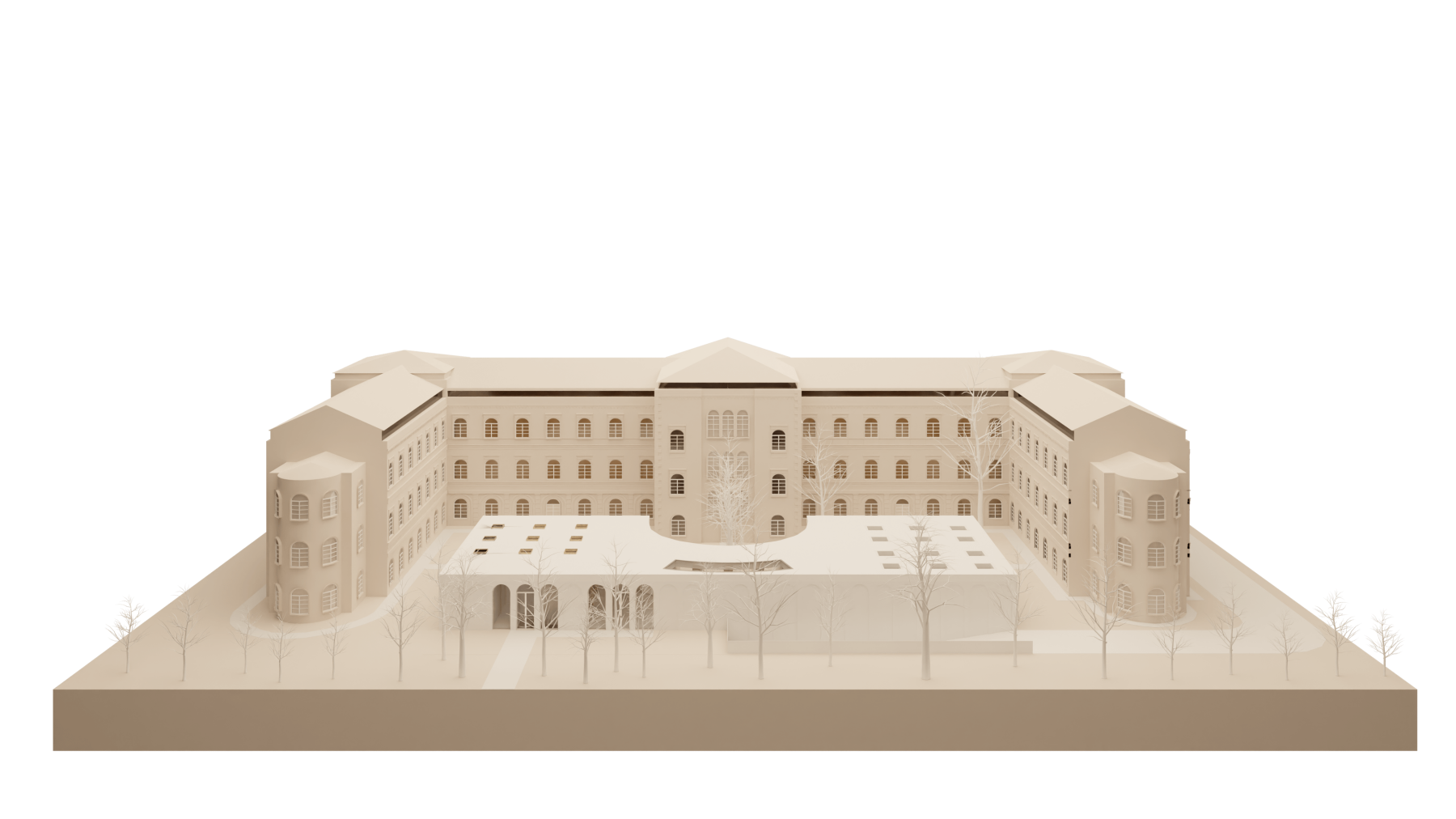

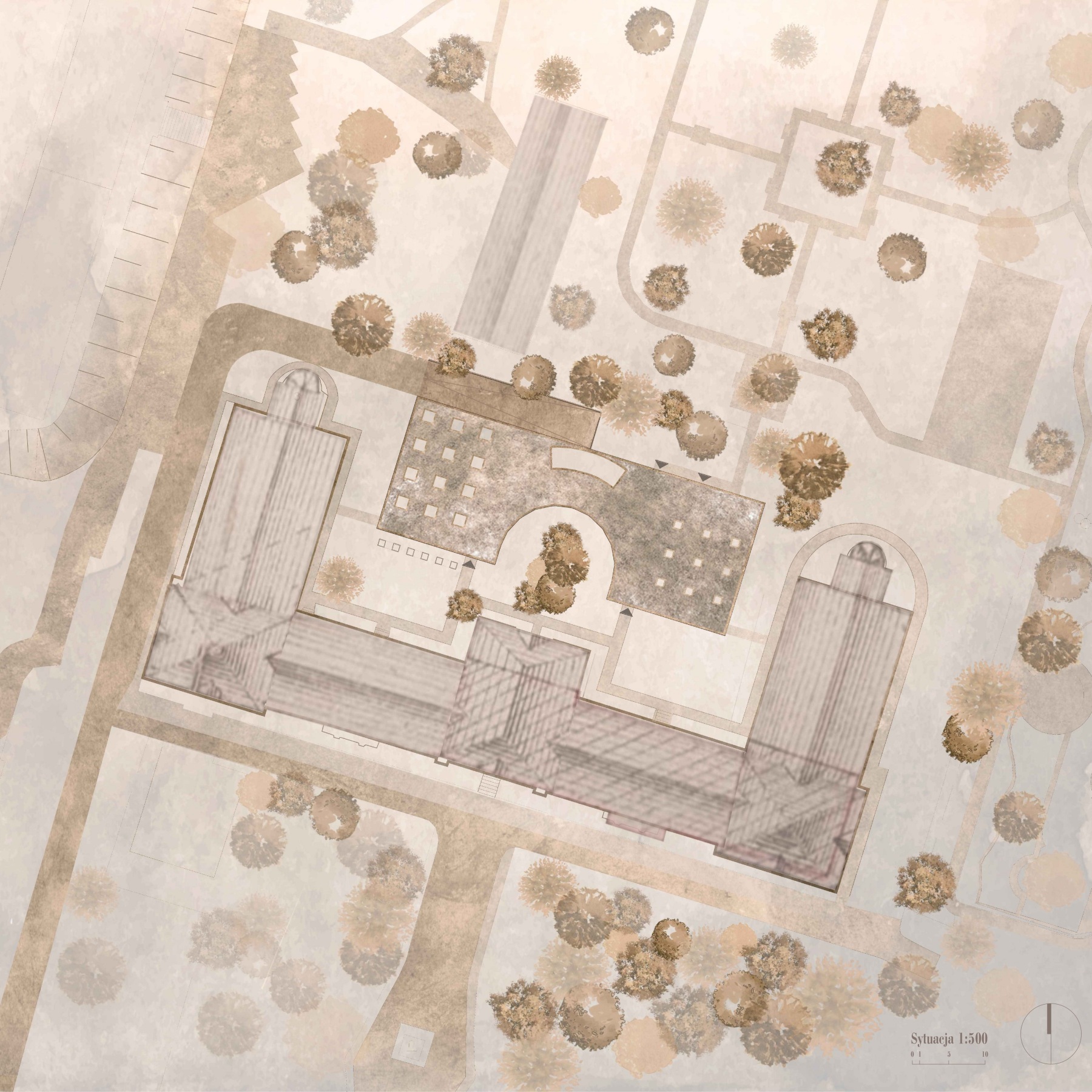

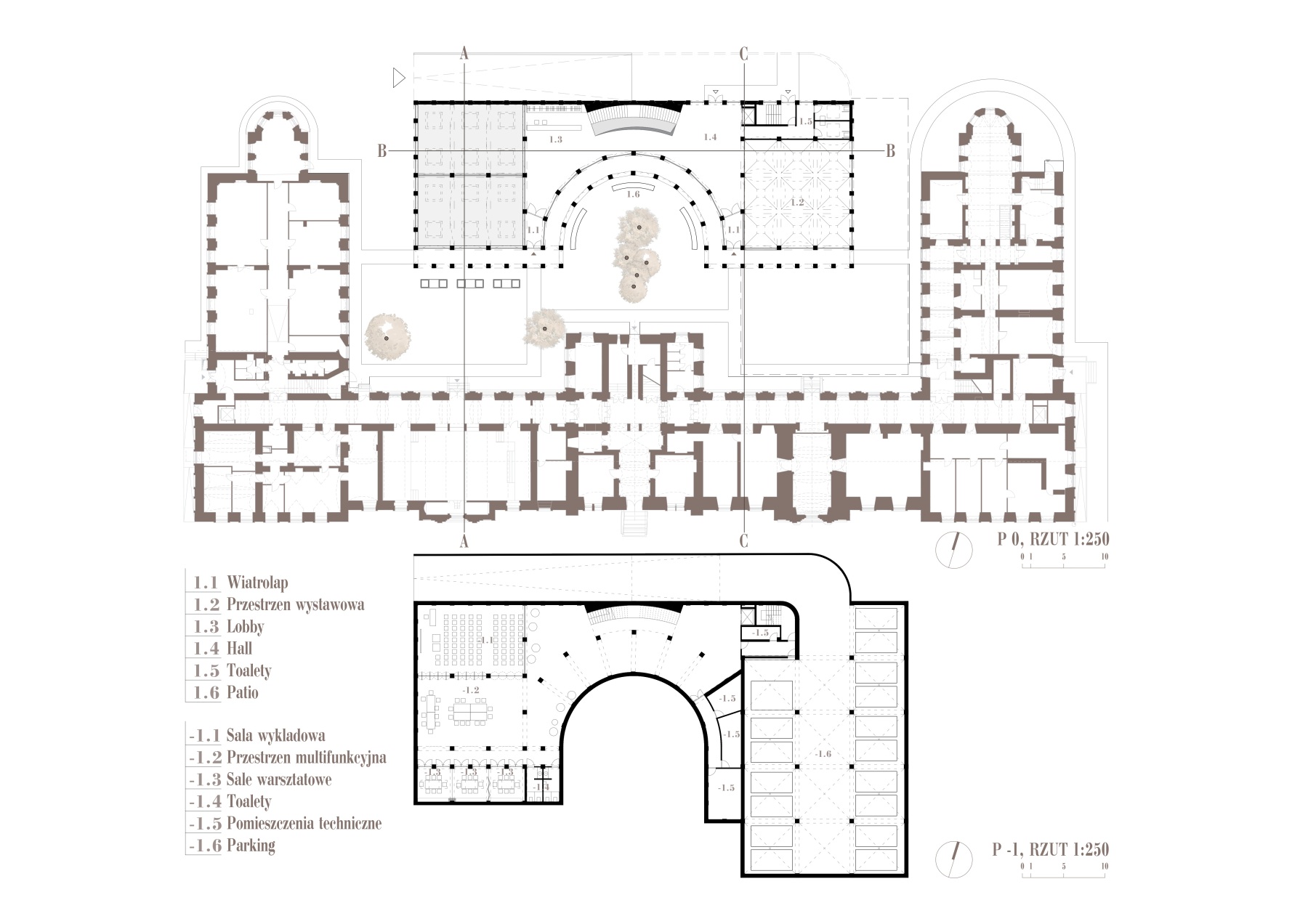

The form of the building is in perfect harmony with its purpose. The two entrances, located on either side of a semi-circular patio designed along the axis of symmetry of the existing palace, lead to a central area which acts as a spacious hall with an impressive staircase. This space connects the two wings of the building. The inner courtyard, where all existing vegetation has been preserved, is transformed into a seasonally accessible space for students. Tree crowns like green umbrellas provide shade in the summer months and improve the microclimate.

Each side of the building has distinct functions. The left wing, as a space dedicated to education, serves as an auditorium, a multi-purpose hall and workshops. The flexible space allows for versatile adaptations according to specific needs. The introduction of natural light through skylights, arched expanses of windows and vaulted ceilings give the space a cathedral-like character. The size of the space is intended to inspire the young architects, placing half of its functions underground ensures that the scale of the building does not dominate the existing structure externally, maintaining a more human scale, while creating a monumental and cathedral-like space inside.

The right side of the building has been planned as a space open to the courtyard, ideal for displaying works and holding exhibitions. On the north side, a functional block has been designed consisting of a lift, an alternative staircase and toilets. Descending along this elevation on a ramp, we can reach the car park, strategically placed underground to minimise the presence of cars in the courtyard. The underground level contains many of the service rooms necessary for the proper functioning of the building.

The roof is usually the most overlooked element of a project, often disfigured by various installations. This is not the case with this building. The design of the roof was integral to this project, as it is visible from the windows of the upper floors of the existing building, effectively acting as a fifth elevation. Covered entirely in lush vegetation, the roof stands out as a distinctive feature. The inclusion of greenery on the roof has numerous environmental benefits. Not only does it contribute to an aesthetically pleasing appearance, it also offers advantages such as temperature regulation, improved insulation and the promotion of biodiversity. Its plane is broken only by carefully placed skylights, creating a rhythmic pattern of square openings. These openings serve the dual function of breaking up the monotony of the greenery and allowing natural light to enter below. The result is a harmonious combination of sustainable design and visual interest, turning what is often an overlooked site into a compelling element of architectural expression.

The design concept draws inspiration from Plato’s cave, an immersion in the underworld, symbolising a journey into the realm of knowledge and architecture. Being underground isolates individuals, allowing them to immerse themselves in the play of light from above (zenithal light) and focus on learning. The building portrays this philosophical journey, where immersion in the darkness leads to enlightenment and coming into the light of day signifies a newfound understanding of the world.

source: Jakub Masłowski

Read also: Krakow | Curiosities | History | Renovation | Education | whiteMAD on Instagram